A short history of Average Good Looks by Average Good Looks

In June 1991, on Lesbian and Gay Pride Day, a murder was committed on the banks of the Assiniboine river, a popular and well-known cruising area for gay men in Winnipeg. It was a tragedy marked by many layers of silence witnessed by apartment dwellers on nearby balconies and gay men who were cruising in the area that night. Four youths armed with sticks beat Gordon Kuhtey, threw his body in the river, and escaped while many people watched and did nothing.

Moved by the circumstances of Gordon Kuhtey’s murder, visual artists Calvin Asmundson and Sheila Spence wanted to respond to it in a way that would reach more people than a traditional gallery venue. The plan emerged to create a billboard image for display on a structure owned by Plug-In Gallery, a Winnipeg artist-run centre. At that time, Wayne Baerwaldt, the director of Plug-In, unequivocally supported the idea.

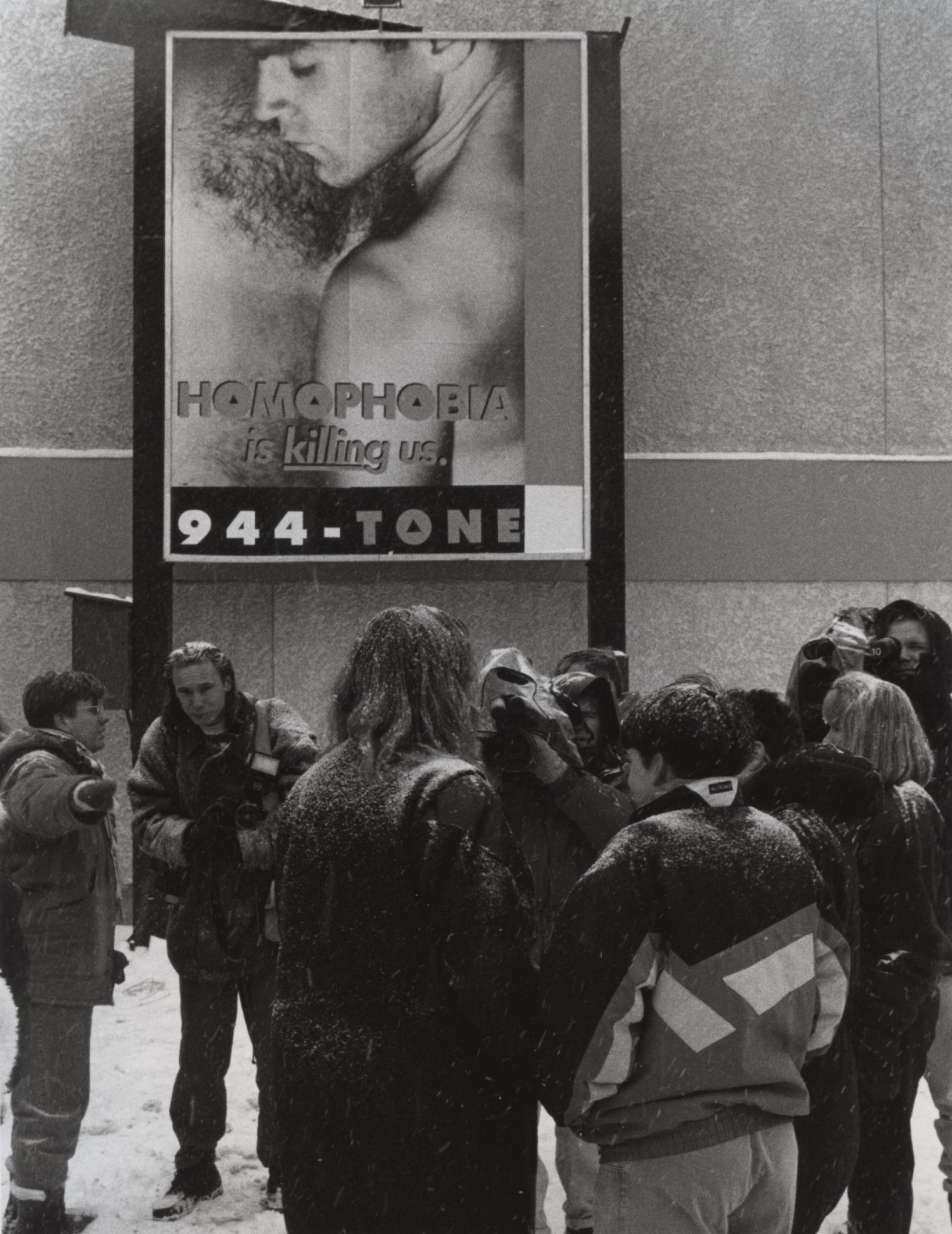

The photographic image selected was out of was of a man’s face in profile against another man’s chest with the text “Homophobia is Killing Us.” Planned to target a broad audience, a phone number was included on the billboard, connected to an answering machine, to encourage discourse with the public as well as to gather statistical and anecdotal information about homophobic violence. Cartoonist and graphic designer, Noreen Stevens was approached to create a layout for the billboard and oversee its production. She arranged to have it printed and installed by Mediacom, a national outdoor advertising company. However, within hours of forwarding camera-ready art to Mediacom, Stevens received a fax refusing involvement in the project because of the potentially offensive nature of the photograph.

Media com’s refusal to print and install the Homophobia is Killing Us billboard set off a chain of events that has led the artists involved in directions they had not envisioned. In that moment, an idea that had its roots in emotion and expression exploded into a determined political force. Frustrated at their efforts to speak out about homophobia being silenced by homophobia, the artists, in conjunction with the Coalition Against Homophobic Violence (CAHV) issued a press release. The story received extensive local and national coverage in the mainstream print and television media, the lesbian and gay press, and the advertising industry press. Ironically, the billboard photograph that Mediacom had wanted to withhold from the public was more widely seen in those days following the press release than it ever would have been installed on the billboard. Without having installed the billboard the envisioned potential for discourse was being fully realized.

Spurred by the positive media coverage the artists and CAHV filed a complaint against Mediacom with the Manitoba Human Rights Commission citing discrimination based on sexual orientation. After a seven-hour negotiating meeting, a settlement was reached which would allow the artists to create two more billboard projects, one on the Plug In structure and the second on various Mediacom-owned structures. Lesbian. It’s not a dirty word, (December 1992) and Gays and Lesbians. Our family. Your family. (August 1993) were largely subsidized by Mediacom, who showed courage, support, and understanding of the artists not long after sitting opposite them at the negotiating table.

At the same time, the artists arranged an alternative an alternate printer and installer for the Homophobia . . . billboard and on December 13th, 1991, four months later than planned, it was unveiled. It received a second wave of extensive media coverage and the phone line at Plug In was ringing night and day, recording hundreds of calls, some positive but mostly violent and negative.

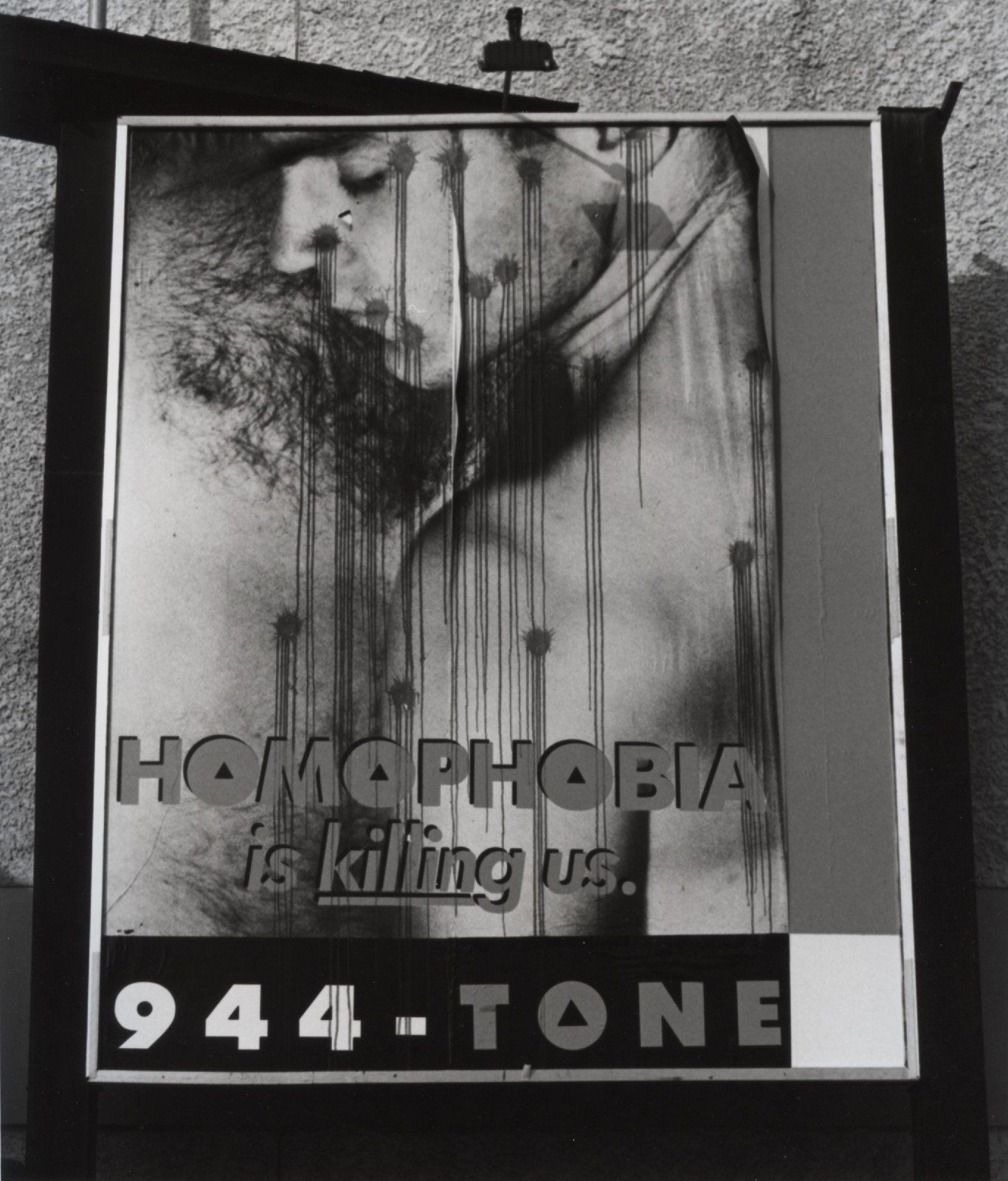

Four days after installation the Billboard was paint bombed and the answering message was altered by remote access to give callers a racist and homophobic message. Three members of the KKK were subsequently charged with public mischief. The paint bombing, while frustrating, added new dimension to the Billboard message, made stronger by the appearance of bleeding bullet wounds on the men in the photograph. It received media attention for the third time.

The project was taking an emotional toll on those involved. Calvin Asmundson faced pressure from his partner to end his involvement with the work. Noreen Stevens and Sheila Spence continued to work under the name Average Good Looks to protect their privacy and individual identities.

From the feedback on this project Noreen Stevens and Sheila Spence, aka Average Good Looks, identified a need to break the silence about gays and lesbians in the most public and widely accessible ways possible. The billboard projects provoked considerable media coverage which served as a catalyst for discussion on a topic rarely acknowledged as a social and political force in our culture.